INTRODUCTION:

The idea of being a citizen perhaps has never in the short history of this nation been so much debated and discussed as the present times; from parks, to streets, to academic institutions, to the news rooms and drawing rooms, the ideas of citizenship and the Constitution are being contested everyday and almost everywhere.

The idea of being a citizen perhaps has never in the short history of this nation been so much debated and discussed as the present times; from parks, to streets, to academic institutions, to the news rooms and drawing rooms, the ideas of citizenship and the Constitution are being contested everyday and almost everywhere.

In the wake of the devastation of World War II, the Bengal famine and the catastrophe of Partition, and as the culmination of the long striving and struggle of the Indian people against colonial rule, the Indian republic and a constitutional democracy came into being some 70 years back. They came with a promise to wipe out the memory of colonial rule, in which most Indians were rendered as lesser beings in their own land. The new republic and its Constitution promised welfare and freedom for all, respect for life, liberty, dignity and opportunities for every individual to realise his/her potential without any discrimination based on the chance of birth. It promised the citizens equality, freedom to conduct their own affairs and speak their minds, as well as protection from discrimination and exploitation. In the form of ‘directive principles’, the Constitution proclaimed a vision of justice, development, welfare and prosperity for each individual, for which the new nation-state was supposed to strive after the war, famine, partition and the long period of colonial rule. It also provided for an elaborate structure of State machinery to achieve these objectives.

We will not discuss here the efficacy of the Constitution in light of our lived experiences of 70 years. Nor will we discuss the recent amendments regarding who can be awarded the citizenship of the country and how this will be done, or not done, through the National Population Register (NPR) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC). We will also not get into the debate about the prognosis for those whose names may not figure in the right lists.

While skipping the present contested socio-political terrain on citizenship, we will look for an answer to a question that is relevant for our immediate future (and perhaps the present too) once we get our certificates to the Promised Land. In the present debate on citizenship and the alleged proliferation of illegal immigrants, there appears to be a whispering campaign that economic benefits are not reaching the right people, not because there is any slackening on the part of the State, but as ‘there are too many people’, especially since undeserving, illegal infiltrators are (it is claimed) cornering much of those efforts and resources. After all, what else could justify the rulers’ extraordinary focus on this question, at the cost of all other material questions facing the nation? In which case, we need to examine how resources are distributed in the country and how that distribution is changing over the years. We take up that question below.

II. Distribution of Wealth and Income in India

When we begin examining the distribution of economic resources across various strata in the economy, its most striking feature is the mindboggling level of concentration right at the very top. In January 2020 the British development institution Oxfam released its annual report on the global distribution of wealth and income, which found that in India the distribution is one of the most extreme, even among the very high concentration levels globally. It found that India’s richest 1 per cent hold more than four times the wealth held by 953 million people who make up the bottom 70 per cent of the country’s population, while the combined total wealth of the top 63 Indian billionaires is higher than the total Union Budget of India for the fiscal year 2018-19, which was Rs 24 lakh crore. The report calculates that it would take a female domestic worker 22,277 years to earn what a top CEO of a technology company makes in one year. With earnings pegged at Rs 106 per second, a tech CEO would make more in 10 minutes than a domestic worker would make in a year.

One might attempt to reconcile oneself to such inequality if the gaps were narrowing and the poor were catching up, but exactly the opposite is the case. Oxfam found that 73 per cent of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest 1 per cent, while 670 million Indians who comprise the poorest half of the population saw only a 1 per cent increase in their wealth. The number of dollar billionaires in India has risen steadily from 9 in 2000 to 131 in 2018. Between 2018 and 2022, India is projected to produce 70 new dollar millionaires every day. The world’s most expensive private residence is in India, where the richest Indian, Mr Mukesh Ambani, lives in a 27-story Mumbai skyscraper valued at $ 1 billion (close to Rs. 7,500 crore by present exchange rate).

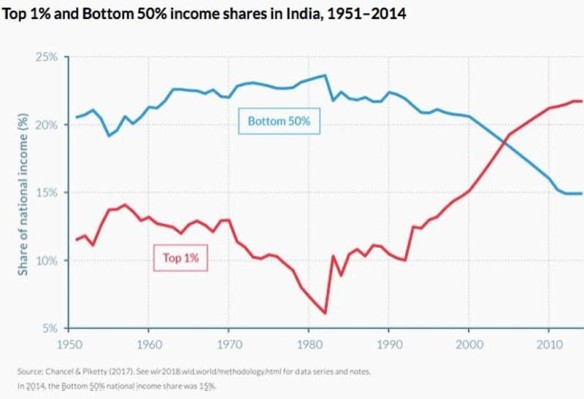

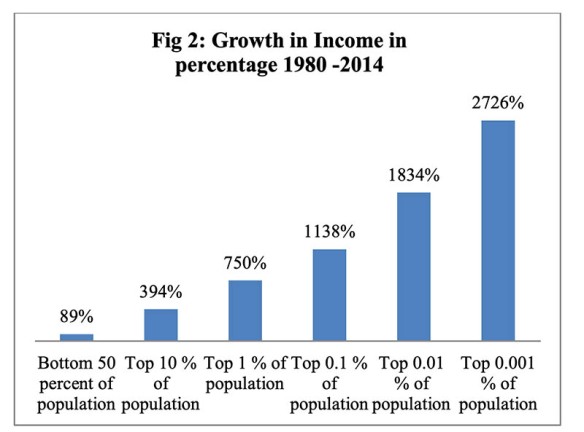

Indeed, India at present is seeing inequalities that perhaps it has never seen in its recorded history, not even during the British Raj. Chancel and Piketty combine historical and tax data with household surveys and national accounts data in order to produce one of the most authoritative estimates of the full distribution of adult pre-tax income in India. They find that the share of national income accruing to the top 1 per cent of income earners is now at its highest levels since the creation of the Indian income tax in 1922. “The top 1 per cent of earners captured less than 21 per cent of total income in the late 1930s, before dropping to 6 per cent in the early 1980s and rising to 22 per cent today,” they state. At the same time the income share of the bottom 50 per cent has seen a steady decline since the 1980s, and is now at its lowest in the last sixty years (see Figure 1 below). According to the authors, India has one of the highest increases in top 1 per cent income share concentration over the past thirty years. While the income of the bottom 50 per cent could not even double over more than three decades after 1980, years of some of the highest GDP growth rates, the income of the top .001 per cent increased by more than 27 times (Figure 2)!

Figure 1

Figure 2

Source: Chancel and Piketty, 2017

III. Tax Collection from the Richest

Some may argue that we should not grudge the rich their income and wealth; the way forward is to have appropriate tax instruments so that we can implement suitable welfare policies in a poor country like India. We will examine in this section the record of taxation of the rich and the corporate sector in India and how it has been changing in recent years.

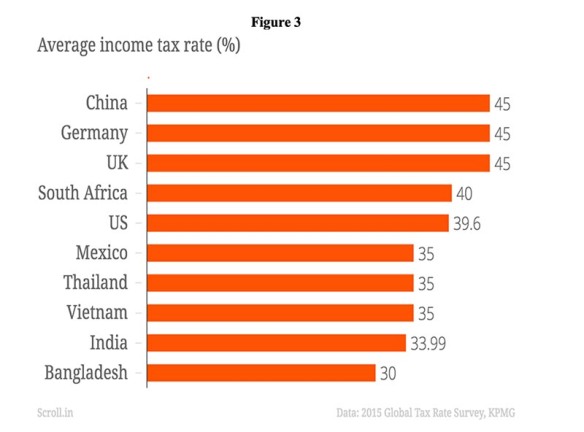

The big picture here again is appalling. While the rich have been accumulating wealth as if there were no tomorrow, a weak tax regime has been increasingly further liberalised for them. The tax rates for the rich have been progressively coming down in the name of incentivising them to spend and invest. At present the effective corporate tax rate for domestic companies in India stands at 25.17 per cent, inclusive of all surcharges and cess. The statutory rate has been brought down steeply last year, by almost 10 per cent, in the name of addressing the slowing economic growth. The new corporate tax rates are much lower than the personal tax rates in the highest bracket, that stand at 30 per cent. Even by international standards the income tax rates are significantly lower in India (Figure 3. In comparison to average income tax rates of 45 per cent in countries like Germany, UK and China, in India the rate was 33 per cent in 2015.

Figure 3

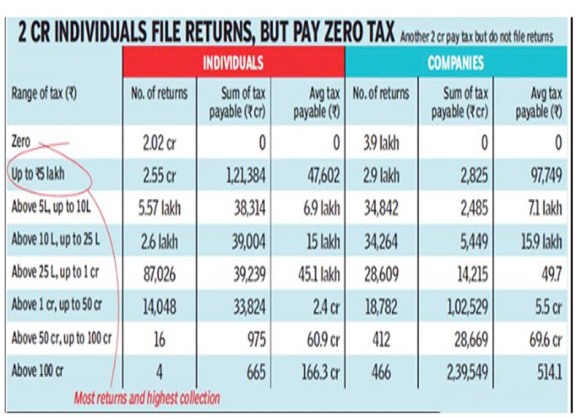

Figure 4: Missing Millionaires of India Figure borrowed from: ET Online|, Oct 23, 2018

Figure borrowed from: ET Online|, Oct 23, 2018

Low tax rates are only part of the problem. Perhaps much greater is the very low number of those who pay taxes in the upper brackets, a great puzzle that is hardly being debated. According to an Economic Times report of 2018 based on the Income Tax department data, out of the 4.8 crore tax returns filed, more than 2 crore paid zero tax, and another 2.5 crore paid less than Rs. 5 lakh tax annually. The real mystery is that a mere 14,000 paid more than a crore of tax, and just 20 individuals paid a tax of more than Rs. 50 crore. This, when the Hurun Global Rich List for 2018 estimated that there were 131 dollar billionaires in India. Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report 2019 estimates that there are 7.59 lakh dollar millionaires in India, with a combined wealth of nearly $2.9 trillion, or over Rs 200 lakh crore (at Rs 70/US $). A return of a meagre 5 per cent on their wealth would garner them an income of Rs 10 lakh crore in a year. Where are these millionaires in the income tax data? The Economic Times report further adds that half of all doctors do not pay any taxes and a mere 13,000 nursing homes pay any tax – in an economy in which health is the most thriving and ubiquitous business, besides perhaps education.

Even more shockingly, with such high levels of wealth concentration as mentioned above, there is no wealth tax in the country. It was abolished in 2015 on the argument that the money collected was a mere Rs. 1000-odd crore, much less than the money spent in collecting it. Once again, the all-powerful State somehow tends to become weak-kneed when it comes to disciplining the rich and powerful. Even a rudimentary calculation would demonstrate that a wealth tax as low as 1 per cent for the very rich few thousand at the very top can more than double the tax collection from the wealthy individuals, (for example, on the basis of Credit Suisse’s estimates of wealth, a 1 per cent wealth tax on Indian dollar millionaires would yield Rs 2 lakh crore) but that is farthest from the agenda of the Government.

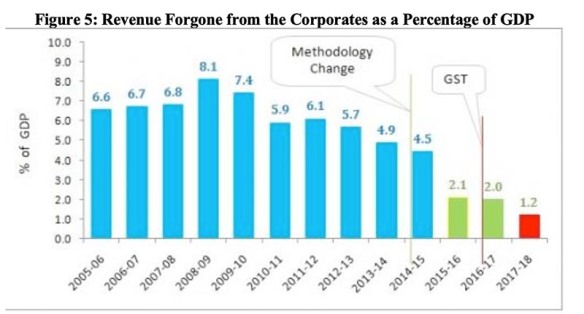

Figure 5: Revenue Forgone from the Corporates as a Percentage of GDP

Figure borrowed from: Down To Earth, 2019

Low tax rates and flagrant tax evasion are not all. The Government regularly provides what it euphemistically calls ‘tax incentives’ for the corporate sector to encourage them to invest and thrive. The previous UPA government was at least willing to share information regarding such ‘incentives’, and it introduced a section in the Union Budget called ‘revenue forgone’ under the heads of excise, customs and corporate income taxes. In 2005-06 such revenue forgone worked out to be Rs. 2.3 lakh crore, 6.6 per cent of the GDP, and it increased to more than 8 per cent of the GDP (Rs. 4.2 lakh crore) in 2008-09 at the time of the global economic crisis. Since then it has continued to be around 5 per cent of the GDP till the last time the Government reported this data, in 2014-15 (see Figure 5 above).

After 2014-15 the Government changed the method of reporting the revenue forgone, making it appear that there was a steep drop. After 2014-15, the indirect taxes of excise and customs were categorised into two, ‘conditional’ and ‘unconditional’, and the Government decided only to report the conditional one, the idea being that those taxes being forgone as a matter of routine need not be reported here, hence the drop in the reported tax concessions. Such data have become further opaque as excise duty has been subsumed under GST after 2017. In spite of all this reluctance to report the true figure of the so called ‘tax incentives’ in the Budget, in 2018-19 they were reported to be more than Rs 1 lakh crore. But then, in the name of stimulating a stagnant economy, the tax rates were drastically cut for the corporate sector in September 2019. According to the Finance Minister herself, it was supposed to provide an ‘incentive’ of another Rs. 1.45 lakh crore. And this is not all of the tax ‘incentives’ available to the corporate sector. Tens of thousands of crores of unpaid taxes by the likes of Reliance, Adani, Vodafone are disputed and arbitrated for decades, rendering the whole tax instrument toothless when it comes to exercising it against the most powerful and in favour of the weakest. Interestingly, such taxes are forgone in the name of the weakest, some times to save employment, or to save the banks where the hard-earned little savings of the common folk are at stake, and at times to save the cheap services being provided to them. Witness the current controversy since the Supreme Court ruled that the telecom sector had to pay the long withheld and disputed tax dues of close to Rs. 1.5 lakh crore. In spite of repeated rulings by the highest court, what we may end up seeing is waiving of these taxes by the Government and further concessions to ‘bail’ them out.

An important consequence of all this is the fact that a State that appears to be all powerful vis-a-vis the common people, and now endeavours to find infiltrators in every nook and cranny of this large nation, stands on shaky economic pillars (we are not going here into the debate on how the money that it collects is spent, and whether that can be better spent). One indicator of the size of Government and its economic resources is the tax to GDP ratio, and not very surprisingly, India’s is one of the lowest among the comparable nations. At present it is close to 17 per cent, and that includes the tax collections at all the three levels, Centre, state and municipal government. Compare this figure with the OECD average of greater than 34 per cent. Even among the large developing countries, the figure for China is close to 24 per cent and for Brazil greater than 32 per cent. It is noteworthy that the figure for India is practically stagnant in spite of rapid economic growth in the 1990s and 2000s. Another important measure of tax policy, especially a progressive policy, is the ratio of direct to indirect taxes in the total tax collection. Direct tax is directly collected from individuals and corporations based on income or wealth, and hence it is possible to tax the richer sections more than the relatively less well off people. On the other hand, indirect tax, such as GST, is collected from producers but is indirectly paid by consumers. Hence the rate of tax is uniform for the rich and the poor. While one may argue that in a country like India, where there is such a skewed distribution of income and wealth, the share of direct taxes should be much greater, the reality is exactly opposite, with the share of direct taxes shockingly as low as 35 per cent. For OECD countries the ratio is exactly reverse, with close to 65 per cent coming from direct taxes. Even for countries like Brazil and Mexico, the figure is greater than 60 per cent for direct taxes.

We need to keep in mind that these estimates are based only on the disclosed incomes and wealth from various sources. According to recent estimates, such unaccounted income can be even higher than 3/4th of the official GDP. Thus, according to economist Arun Kumar, one of the leading authorities on black economy in India, it could be as high as Rs. 144 lakh crore last year (almost six times the total Budget of the all powerful Central Government of India!), mostly accruing to the highest strata (on which no taxes need to be paid), thus further very drastically skewing the distribution in favour of the very richest and most powerful.

IV. Bank Credit and its Distribution

If the poor have neither income nor access to State welfare measures based on taxation of the rich, perhaps their last resort is access to credit, especially in an economy where formal jobs are so few and increasingly difficult to come by and most people are either self-employed or work in micro and small units across the three sectors of the economy. When the banks were nationalised some fifty years back, the expectation was that small savings of the common people would be channelised for their welfare. But the actual reality is far from it. Around 96,000 individual corporate borrowers have a credit exposure of Rs 5 crore or more from the banking system, totalling about Rs 98 lakh crore. Out of this, more than Rs 40 lakh crore is the exposure of a mere 266 corporate entities, and close to Rs 62 lakh crore that of a mere 1300 entities. Thus while the savings of the poorest may be harnessed, they finally mostly end up being in the hands of a minuscule set of powerful corporate actors. According to a Credit Suisse report of 2015, the loans of the top 10 corporate houses, which included names like Reliance, Adani and Vedanta, added up to 12 per cent of the loans in the banking system in India and 27 per cent of all corporate loans.

We could have drawn some solace if this humongous credit to the big corporate houses were being productively deployed, but the reality is dismal. We increasingly see headlines about so-called ‘non performing assets (NPAs)’, meaning thereby that either the principal amounts and/or the interest due are not being returned to the lending bank. According to the RBI, a non-performing asset is a loan or advance for which the principal or interest payment remained overdue for a period of 90 days. For more than a decade now NPAs have been piling up in the books of the banks, and had reached more than Rs 10 lakh crore at the end of 2018, 11.2 per cent of all the advances made by the commercial banks in India. Predominantly this figure was due to advances made to the corporate sector, that too the sectors where large corporate houses operate such as steel, power and other infrastructure-related sectors such as telecom, cement, construction, transport, mining and automobiles. Nearly 50 per cent, almost Rs 4.5 lakh crore worth, of the NPAs were due to loans to the top 100 borrowers, an RTI query filed by The Wire revealed; this meant that on average, each of the top 100 borrowers was responsible for NPAs worth Rs 4,500 crore. The RBI has consistently refused to name the borrowers whose accounts have turned NPAs. Instead of holding such borrowers accountable, the banking establishment has meekly surrendered to them for all practical purposes, and has only been window dressing its accounts to appear as if it has been doing something. The most tangible action that they have taken is writing off these loans at a massive scale, that means practically any hope of these loans and dues being paid back is close to zero. Close to Rs. 5 lakh crore worth of such corporate loans have been written off during 2016-19 according to RBI data, and the government would like us to believe that the NPA situation is under control! Even before such massive write-offs, former RBI deputy governor KC Chakrabarty in 2016 called “(t)hese write-offs… the biggest scandal of the century.” Nor is this the end. A recent India Ratings report warned that at least Rs 10.52 lakh crore worth of corporate loans – around 16 per cent of the system-level corporate debt – may default over the next three years due to the prolonged slowdown in the Indian economy.

V. Rapid Flight of the Rich and their Riches

While the rulers hunt alleged ‘infiltrators’ and see that they are shunted out to wherever, the rich and their riches increasingly seem to be escaping the shores of the nation. Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington based think-tank, ranked India third globally in illicit wealth outflows in 2012. In that year India witnessed illicit outflows of an estimated $94.76 billion, or 5.2 per cent of its GDP. Further, GFI estimated that the cumulative illicit money moving out of the country over a ten-year period from 2003 to 2012 was $440 billion (Rs 28 lakh crore in 2014 when the report was released). This was almost double of the much-sought net foreign direct investment (FDI) received during the same period, according to World Bank figures.The latest GFI data indicate that merchandise trade-related illicit financial flows from India were $83.5 billion for the year 2017; this excludes a number of other important forms of illicit flows, for lack of data.

Not only is the money of the rich flying abroad, but they themselves too, in hordes, seem to be keen to escape the nation. At least 23,000 dollar-millionaires have left India between 2014 and 2017, according to data cited by Morgan Stanley; 2.1 per cent of India’s rich left the country in 2017 alone. In fact, India lost the highest percentage of ‘high net worth individuals’ (HNWI) – those with net assets of more than $1 million – to migration since 2014, the report adds. A later report titled ‘Global Wealth Migration Review 2019’ found that another 2 per cent of India’s total High Net-worth Individuals, that account for nearly 6,000 dollar millionaires, migrated from India in 2018. These numbers included 36 big-ticket ‘economic offenders’ – such as Vijay Mallya, Nirav Modi and others – who have fled the country, as the Government itself admitted in the Rajya Sabha. Together, these individuals are responsible for defrauding the public exchequer of an estimated Rs. 40,000 crore of public funds. Between 2014 and 2017, 4.5 lakh Indians opted for citizenship of another country, as several foreign countries offer easy citizenship in exchange for cash and investments.

Apparently 8 lakh professionals, an overwhelming majority of them Indians, are seeking employment-based green cards in the US that would allow them to stay in the US permanently; for those who apply now, the wait is likely to be as long as 50 years.

Apparently 8 lakh professionals, an overwhelming majority of them Indians, are seeking employment-based green cards in the US that would allow them to stay in the US permanently; for those who apply now, the wait is likely to be as long as 50 years.

Paradoxically, as these most wealthy and influential of Indians leave the shores of the country, they become even more celebrated and acceptable for the Indian establishment. Some become advisers to the Indian government at various levels and adorn so-called ‘think tanks’. For instance, Prof. Arvind Panagariya, the first Vice-Chair of the newly-made policy body Niti Aayog during the first term of PM Modi, enjoyed dual citizenship according to newspaper reports, though India still does not legally allow a dual citizenship. The well-known ‘nationalist’ actor, Akshay Kumar, very close to the present establishment, holds a Canadian passport. If the Prime Minister can woo the so called NRIs in US or UK during his visits, it increases manifold his legitimacy and popularity among the urban upper middle class back home.

The wealth of the country is generated in farms, mines and factories by those who do not get even a pittance for their toil, and get nothing from the State in the form of security. We saw this amply during demonetisation, and now, with the nationwide lockdown due to the COVID 19 virus scare, they are left to fend for themselves or are hunted down like criminals. It is these people’s lives that the State and ruling establishment increasingly want to control through various surveillance mechanisms — CCTVs at workplaces and public places, mechanisms like Aadhar and PAN, and sweeping top-down measures like demonetisation, GST and now with the new ideas of citizenship. The working classes will be further driven to insecurity so that they are willing to work and live in starvation conditions while the rich and powerful can appropriate all the wealth with impunity and without any semblance of accountability.

Today, the questions of citizenship, the Constitution and alleged ‘infiltration’ are the topic of debate everywhere. But the real questions that the nation needs to debate are: why are most of the resources generated by the toil and sweat of the common people cornered by a minuscule elite; and why is the State so unconcerned about holding the latter accountable for what they do with their massive incomes and wealth?

No comments:

Post a Comment